Britomartis

The Supreme Mother God Rewritten

The history of Britomartis is a classic case of the patriarchal reduction of the Supreme Mother God to an inferior character within a male-centred drama.

According to Wikipedia:

The oldest aspect of the Cretan Goddess was as Mother of Mountains, who appears on Minoan seals with the demonic features of a Gorgon, accompanied by the double-axes of power and gripping divine snakes. Her terror-inspiring aspect was softened by calling her Britomartis, the "good virgin", a euphemism to allay her dangerous aspect. Every element of the Classical myths that told of Britomartis served to reduce her power and scope, even literally to entrap her in nets (but only because she "wanted" to be entrapped). The traditional patriarchal bias of Greek writers even made her the "daughter" of Zeus, rather than his patroness when he was an infant in her cave on Mount Dikte, and they made her own tamed, "evolved" and cultured Olympian aspect, the huntress Artemis, responsible for granting Britomartis goddess status, a mythic inversion. But the ancient goddess never quite disappeared and remained on the coins of Cretan cities, as herself or as Diktynna, the goddess of Mount Dikte.Various points need to be made here. Crete, as is well known, was one of the last civilisations to hold out against the patriarchal revolution. Thus Britomartis remained as a pure image of Our Mother God until a relatively late stage in history.

Her association with the Sacred Mountain is important, since the sacred mountain holds a central position in many ancient traditions – Mount Fuji, Mount Sinai, Mount Olympus, Mount Everest (known in Tibet, where many pre-patriarchal traditions survive, as Qomolangma: "Mother of the Universe") are well-known examples.

The Sacred Mountain is the place where Earth touches Heaven, and thus the symbolic earthly home of the Supreme Divine.

The ferocious (or misnamed "demonic") aspect is akin to the fearsome aspects of Durga, the warrior-mother who protects Her children against real demons.

As is discussed in our pages on Durga, in times of danger and distress, this aspect of Dea sometimes comes to the fore; and we may suspect that, with the Queenly civilisation of Crete increasingly surrounded by savage new patriarchal regimes, the Vikhelic, or warlike, aspect of Dea became popular, perhaps inspiring the defence forces of the Cretan motherland.

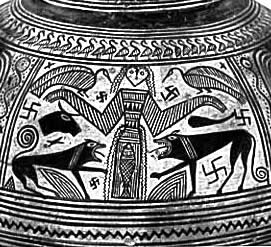

The twin serpents and the double-axe, or labrys are both symbols of the duality of manifestation and its transcendence by Deity. The two crescent-heads of the axe are joined by the haft which represents the world-axis, while the two snakes are centred by the staff, or caduceus of Wisdom, or, in most Cretan representations, by the upright body of Dea Herself, or of Her priestess.

In the earliest representations, She is surrounded by feral animals, which represent the earthly deployment of the Celestial Archetypes (each species being the embodiment of a Divine Idea). Thus She is the Mother-Creatrix.

As Divine mother, she was later shown suckling Zeus, but originally she suckled gryphons – a symbol of feminine wisdom and solarity, and also – perhaps as part of Her Vikhelic or Durga-like nature – of retribution.

Some scholars have suggested that, rather than being the same Deity as Diktynna, Britomartis and Diktynna originally had the same relationship as Demeter and Persephone. This would make Britomartis's cultus a Cretan version of the Mother-Daughter religion.

Curiously, Spenser, in The Faerie Queene adopts Britomartis as an allegorical figure of the virgin Knight of Chastity, representing English virtue – in particular English military power – through a newly-coined etymology that associated Brit – as in Britain – with Martis, here thought as of Mars, the Roman war god – the masculinised form of Sai Vikhë. In Spenser's allegory, Britomart connotes the Virgin Queen, Elizabeth I of England.

This "false" etymology is not quite as misleading as it seems, given the extraordinary power of words to revert to their ancient meanings: language being, in its deepest essence, metaphysical.

The name Britain itself derives ultimately from the Brigantia/Brighde/Brigit group of names for the Supreme Mother God, while the martial element correctly returns this Name of Dea to her original fearsome, vikhelic aspect. And once again, as in the beginning, She is associated with the image of a virgin warrior-queen.

To the literalistic modern scholar this may seem like mere coincidence, but to those whose knowledge goes a little deeper, this is but another instance of the more-than-material power of Name and Form: and particularly the sacred Names and Forms of Our dear Mother God.

Send Questions or Comments on Britomartis

Chapel of Our Mother God Homepage

All written material on this site is copyright. Should you wish to reproduce any portion please contact us for permission.

The Many Names of Dea

Gospel of Our Mother God

The Gospel of Our Mother God is a collection of inspirational texts, prayers and daily inspiration for the Mother-Faith devotee or household.

The Feminine Universe

The Other Philosophy

Everything you have ever heard comes out of the patriarchal world-view. Its materialism, its religion, even its feminism. Here is the other way of seeing the world; the natural way: the way that everyone saw things before patriarchy and will again when patriarchy is long forgotten.